Should freight be fast tracked?

The United States is a nation connected by airports and interstate highways. An enormous volume of freight moves by rail, but passenger rail, particularly over longer distances, has never been prioritized like it has in Europe and Asia. But it seems that change is on the way.

But should high-speed passenger rail networks also be used for freight?

We surveyed 105 senior decision-makers involved in high-speed rail projects around the world and asked them this very question.

The majority are in favor.

This result is notable given that the prospects for high-speed rail freight (HSRF) have been uncertain in recent years, particularly in Europe. In late 2018 Italian operator Mercitalia Logistics (Gruppo FS Italiane) launched the world’s first high-speed rail service dedicated to freight. Unfortunately, it closed in 2022 owing to low demand, high costs, and strong competition from road and air.

It should be noted that a range of models could be considered for HSRF. From exclusive HSRF infrastructure and rolling stock – which is both the most expensive and least realistic in most cases — to niche models that use parts of existing HSR passenger railcars to accommodate high-value express freight.

Mercitalia employed a model between these extremes, sharing pre-existing, high-speed passenger rail infrastructure, but with rolling stock dedicated to freight. EURO CAREX also advocated for this model under ambitious plans to connect Europe’s major logistics hubs. However this initiative seems to have lost impetus, with little progress reported since 2018.

So, why are so many of our respondents in favor of HSRF?

The compelling case for HSRF

One of the biggest drivers of HSRF adoption is decarbonization. By taking freight off the road and out of the air, we would reduce CO2 emissions significantly. HSRF emits 17 times less pollution than rival modes according to EURO CAREX, cited above.

Then there is speed. In some cases, HSRF could move goods between points faster than any other mode of transportation. This is particularly beneficial for time-sensitive or perishable goods. Businesses could use such services to streamline their supply chains and reduce inventory costs.

HSRF can also add capacity and reduce the burden on other over-stretched freight services, bringing considerable economic benefits. In some scenarios, it may simply help reduce road, rail, or air-traffic congestion on certain corridors, alleviating pressure on those networks to expand capacity.

There are also potential access advantages. HSRF lines could extend express delivery services into rural areas that air freight cannot easily reach. And, since HSR stations often extend deep into congested urban centers, HSRF can complement inner-city logistics services via direct connections to last-mile delivery.

The other side of the debate

If there is such a compelling case for HSRF, why then do almost one-third of our respondents oppose its adoption? As with many good ideas, the challenges lurk in the details.

For instance, in most countries, HSR networks also have limited coverage compared with road or air networks. For longer distances this could be an issue, as using HSRF at scale could require more handovers between modes and networks. Every additional ‘touch’ on the logistics path pushes up costs, while increasing the risk of delays, product degradation or security breaches.

Existing hubs where goods could change modes are often located outside of city centers. HSR hubs in the center of commercial districts might be beneficial for some kinds of urgent freight but it could be a barrier for others. This could include goods destined for industrial areas or those that need to switch transport modes before continuing to their destination.

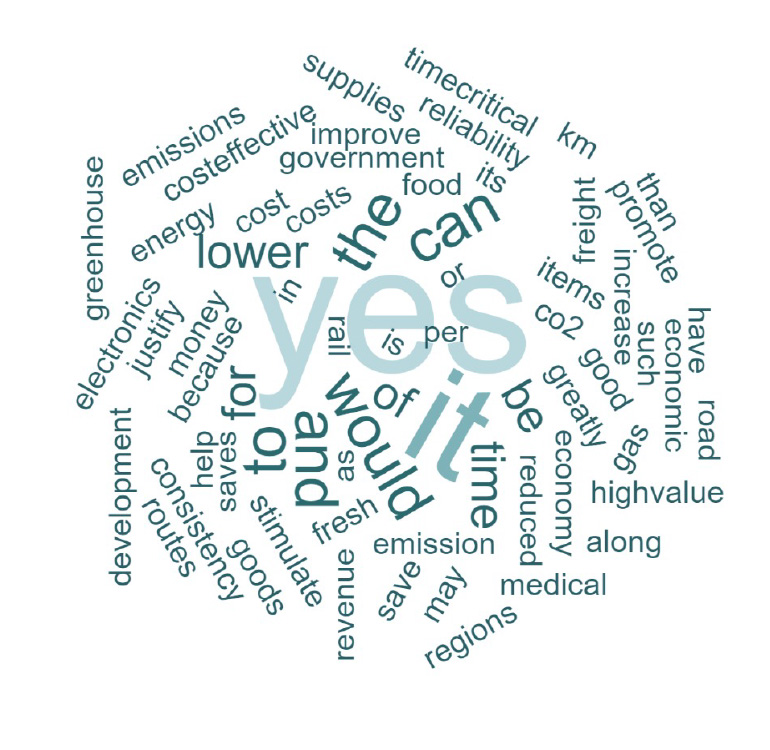

Do you think that high-speed rail should also be used for freight? Words from respondents in favor:

Adding stops on the outskirts of town, just for freight purposes, would likely be unworkable for combined freight and passenger services, though they would work for dedicated models.

Even if an operating model looks certain to work, HSR infrastructure may require significant investment before it can support different services, meeting the high time, cost, reach and reliability service levels of each.

Two major hurdles for HSRF

Our more skeptical respondents were particularly concerned about two issues.

First, they fear that HSRF will be unable to operate competitively with road and air freight. However, costs differ considerably across operating models. In some markets, a dedicated HSRF line may be viable. In others, the HSRF model could integrate seamlessly with an HSR passenger service.

In either case, there are high initial investment costs, which planners would need to justify by indicating areas of added economic and social value. Meanwhile, operational and maintenance costs need to be viable for operators. In most scenarios, premium express services, transporting high value and specialized goods between urban centers, are likely to be the key to making HSRF economic models work.

Secondly, respondents are worried about the impact of HSRF on the passenger services that share the lines and trains. Given that the two types of rail service have such particular requirements and distinctive characteristics, this is a major challenge in terms of the design of both infrastructure and rolling stock.

It takes time to load and unload freight. So in shared models, this could add unacceptable delays for passenger services. Mail bundles and other smaller containers could work, but larger cargo volumes are likely to take too long using current methods.

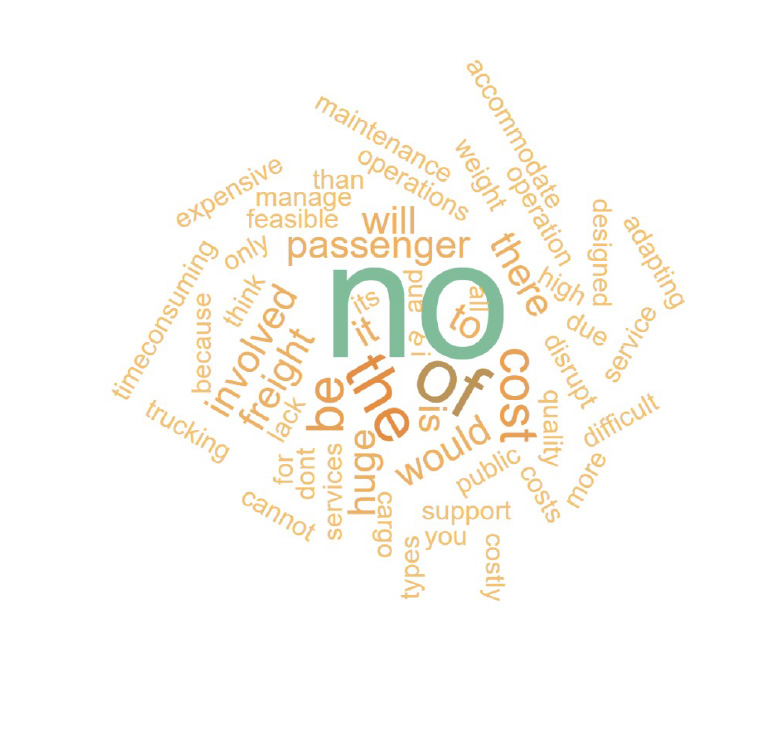

Do you think that high-speed rail should also be used for freight? Words from respondents opposed:

Which HSRF models are working?

Operators have tried several different HSRF models, with mixed results. In France, the SNCF TGV La Poste was a dedicated HSRF service which operated successfully for 31 years, using five bright-yellow TGV Sud-Est half-trainsets. But in 2015, the service was discontinued as the HSRF service was not deemed compatible with La Poste’s new operating model. This new model is centered around standardized swap bodies, compatible with most trucks, trailers and rail cars that move shipping containers. Apart from cost efficiencies, swap bodies allow for goods to change modes quickly and efficiently, without the need for emptying or repacking. However, swap body containers are not easily compatible with streamlined HSR trains, nor are they suited to the dense urban areas where HSR services often originate and end.

A more natural use of containerization for high-speed rail comes from the air cargo sector. These smaller boxes can be transloaded more easily between aircraft and modified HSRF railcars.

A more positive story arises for models that use space on existing passenger services to deliver low-carbon, premium express logistics services. One example is the United Kingdom (U.K.)’s InterCity RailFreight (ICRF), which claims to offer “an all-electric supply chain” but “without the range anxiety or crippling costs.” While largely operating on 125-mile per hour (200-kilometer per hour) trains — outside the qualifying parameters for most HSR definitions — the company is nonetheless proving the viability of a model that, in theory, could be transferred to any HSR network.

One objection to ICRF’s model is that it is too niche, suitable only for transporting small volumes of high-value goods, justifying the cost per unit. But HSRF doesn’t have to move everything from copper to caviar. Gaining a foothold with a viable niche service could be a good strategy and over time ICRF may find many ways to scale and expand.

The future of HSRF

The range of compelling benefits and cogent objections is perhaps why many of those in favor of HSRF gave qualified responses:

“ … only for certain types of freight.”

“ … where safe operation permits.”

“ … the primary focus should be passengers.”

“ … provided the capacity can be split so that there is minimal interaction.”

“ … mixed use can introduce operational difficulties.”

“ … managing space and capacity will be challenging.”

Certainly, not all corridors and not all types of freight are suitable for HSRF. But where suitable, and with a little focused innovation, HSRF models could flourish. New integration opportunities could help to make services viable. ICRF uses bicycle couriers to collect and distribute goods in cities, adding considerable agility, a human touch and a low-carbon footprint. In future, drones and other self-driving vehicles could become useful last-mile workhorses for time-sensitive industrial loads.

But HSRF operators also need to ensure they compete effectively with key rivals. For instance, they need to offer cargo visibility comparable to that of their road and air competitors. Historically, this has been a weakness of rail-freight services. An effective, reliable digital platform and sensor network that provides requisite cargo visibility would be essential to the viability of premium express services.

For all the caveats, however, it seems only a matter of time before we see more success stories in HSRF. As the energy transition continues and the growth in ecommerce drives increased demand for express delivery, more HSR lines will appear, and smart operators will find business models that guide HSRF to its rightful place as a key element in the future of logistics.

From vision to reality

-

Article

![]()

How fast is too fast for high-speed rail?

The right speed for a high-speed rail line comes down to trade-offs among many important factors.How fast is too fast for high-speed rail?The right speed for a high-speed rail line comes down to trade-offs among many important factors. -

Article

![]()

Not a pipe dream? Why high-speed rail has a role in Australia

Long talked about and not yet delivered, high-speed rail is Australia’s long unrealized dream.Not a pipe dream? Why high-speed rail has a role in AustraliaLong talked about and not yet delivered, high-speed rail is Australia’s long unrealized dream.